Author: Najat Kessler

One of our publications is highlighted as the Best of 2014 on mit.edu

Review: DNA Damage and Its Links to Neurodegeneration

The integrity of our genetic material is under constant attack from numerous endogenous and exogenous agents. The consequences of a defective DNA damage response are well studied in proliferating cells, especially with regards to the development of cancer, yet its precise roles in the nervous system are relatively poorly understood. Here we attempt to provide a comprehensive overview of the consequences of genomic instability in the nervous system. We highlight the neuropathology of congenital syndromes that result from mutations in DNA repair factors and underscore the importance of the DNA damage response in neural development. In addition, we describe the findings of recent studies, which reveal that a robust DNA damage response is also intimately connected to aging and the manifestation of age-related neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Video Abstract

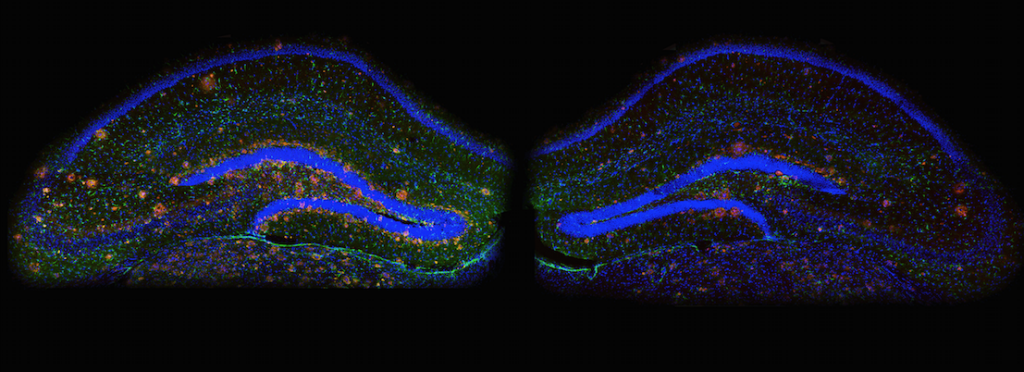

Neuroscientists find that limiting a certain protein in the brain reverses Alzheimer’s symptoms in mice

Limiting a certain protein in the brain reverses Alzheimer’s symptoms in mice, report neuroscientists at MIT’s Picower Intitute for Learning and Memory.

Researchers found that the overproduction of the protein known as p25 may be the culprit behind the sticky protein-fragment clusters that build up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. The work, which was published in the April 10 issue of Cell, could provide a new drug target for the treatment of the disease that affects more than five million Americans, says Li-Huei Tsai, director of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and senior author of the paper.

Drug Tweaks Epigenome to Erase Fear Memories

A hurricane, a car accident, a roadside bomb, a rape — extreme stress is more common than you might think, with an estimated 50 to 60 percent of Americans experiencing it at some point in their lives. About 8 percent of that group will be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. They will have flashbacks and nightmares. They will feel amped up, with nerves on a permanent state of high alert. They won’t be able to forget.

We are featured on the MIT Home Page!

Science In Mind

MIT researchers find a drug that helps erase traumatic memories in mice.

For years, neuroscientist Li-Huei Tsai has been unraveling the brain circuits that underlie memory, searching for approaches that might be helpful in treating Alzheimer’s disease. In 2007, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientist identified an experimental drug that could restore lost memories in mice. Lately, she has been wondering whether that kind of drug might be useful to help people forget traumatic events that cause fear and anxiety.

In a study published Thursday in the journal Cell, Tsai and colleagues used a single dose of the drug, called an HDAC inhibitor, to help mice extinguish a fearful memory of a traumatic event that took place in the distant past.

By Carolyn Y. Johnson / Globe Staff

Erasing traumatic memories

New study identifies drug that could improve treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Nearly 8 million Americans suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition marked by severe anxiety stemming from a traumatic event such as a battle or violent attack.

Many patients undergo psychotherapy designed to help them re-experience their traumatic memory in a safe environment so as to help them make sense of the events and overcome their fear. However, such memories can be so entrenched that this therapy doesn’t always work, especially when the traumatic event occurred many years earlier.

MIT neuroscientists have now shown that they can extinguish well-established traumatic memories in mice by giving them a type of drug called an HDAC2 inhibitor, which makes the brain’s memories more malleable, under the right conditions. Giving this type of drug to human patients receiving psychotherapy may be much more effective than psychotherapy alone, says Li-Huei Tsai, director of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory.

Illustration: Christine Daniloff/MIT

How old memories fade away

Discovery of a gene essential for memory extinction could lead to new PTSD treatments.

If you got beat up by a bully on your walk home from school every day, you would probably become very afraid of the spot where you usually met him. However, if the bully moved out of town, you would gradually cease to fear that area.

Neuroscientists call this phenomenon “memory extinction”: Conditioned responses fade away as older memories are replaced with new experiences.

A new study from MIT reveals a gene that is critical to the process of memory extinction. Enhancing the activity of this gene, known as Tet1, might benefit people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by making it easier to replace fearful memories with more positive associations, says Li-Huei Tsai, director of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory.

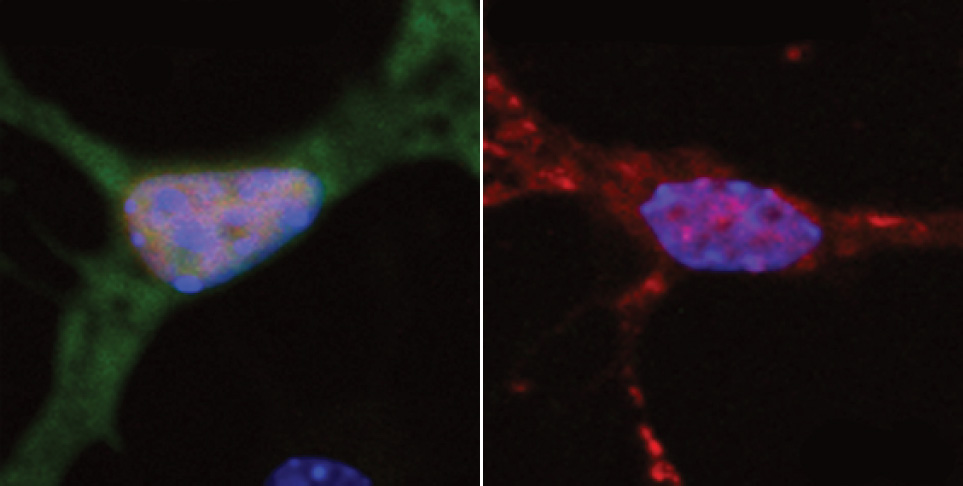

DNA damage may cause ALS

New study finds link between neurons’ inability to repair DNA and neurodegeneration.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) — also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease — is a neurodegenerative disease that destroys the neurons that control muscle movement. There is no cure for ALS, which kills most patients within three to five years of the onset of symptoms, and about 5,600 new cases are diagnosed in the United States each year.

MIT neuroscientists have found new evidence that suggests that a failure to repair damaged DNA could underlie not only ALS, but also other neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. These findings imply that drugs that bolster neurons’ DNA-repair capacity could help ALS patients, says Li-Huei Tsai, director of MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory and senior author of a paper describing the ALS findings in the Sept. 15 issue of Nature Neuroscience.