By developing a lab-engineered model of the human blood-brain barrier (BBB), neuroscientists at MIT’s Picower Institute for Learning and Memory have discovered how the most common Alzheimer’s disease risk gene causes amyloid protein plaques to disrupt the brain’s vasculature and showed they could prevent the damage with medications already approved for human use.

About 25 percent of people have the APOE4 variant of the APOE gene, which puts them at substantially greater risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Almost everyone with Alzheimer’s, and even some elderly people without, suffer from cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a condition in which amyloid protein deposits on blood vessel walls impairs the ability of the BBB to properly transport nutrients, clear out waste and prevent the invasion of pathogens and unwanted substances.

In the new study, published June 8 in Nature Medicine, the researchers pinpointed the specific vascular cell type (pericytes) and molecular pathway (calcineurin/NFAT) through which the APOE4 variant promotes CAA pathology.

The research indicates that in people with the APOE4 variant, pericytes in their vessels churn out too much APOE protein, explained senior author Li-Huei Tsai, Picower Professor of Neuroscience and director of the Picower Institute. APOE causes amyloid proteins, which are more abundant in Alzheimer’s disease, to clump together. Meanwhile, the diseased pericytes’ increased activation of the calcineurin/NFAT molecular pathway appears to encourage the elevated APOE expression.There are already drugs that suppress the pathway. Currently they are used to subdue the immune system after a transplant. When the researchers administered some of those drugs, including cyclosporine A and FK506, to the lab-grown BBBs with the APOE4 variant, they accumulated much less amyloid than untreated ones did.

“We identify that there is a specific genetic pathway that is expressed differently in a population that is susceptible to Alzheimer’s disease,” said study lead author Joel Blanchard, a postdoc in Tsai’s lab. “By identifying this we could identify drugs that change this pathway back to a non-diseased state and correct this outcome that’s associated with Alzheimer’s.”

Building barriers

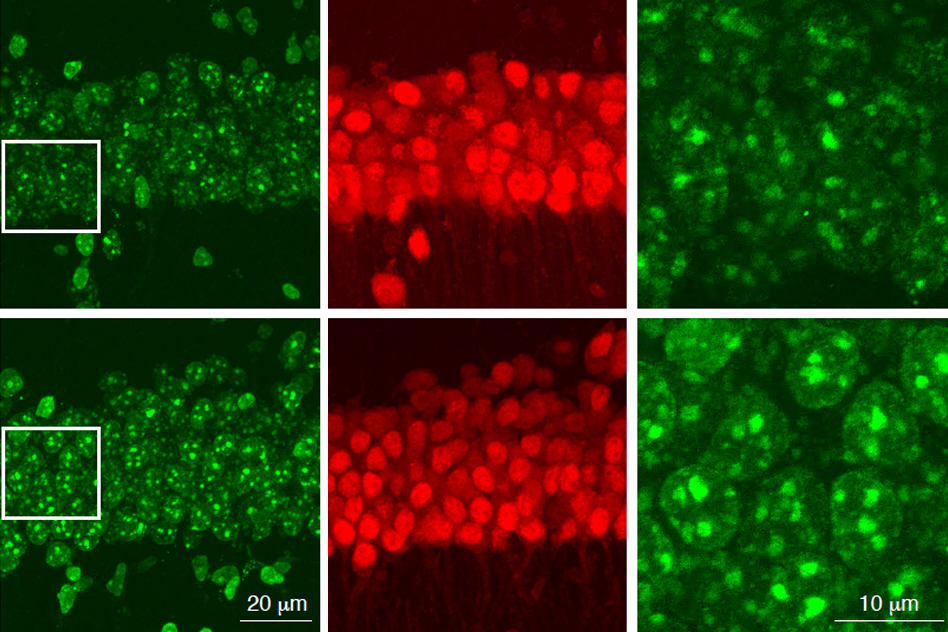

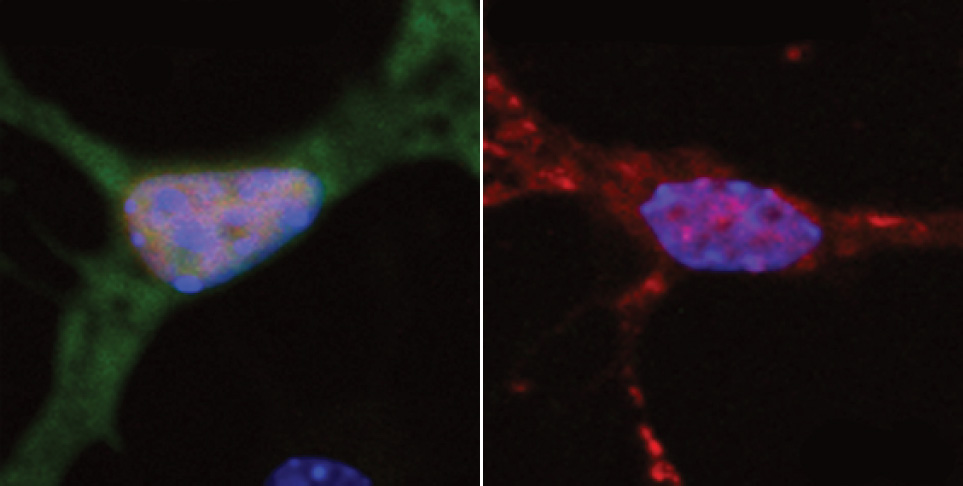

To investigate the connection between Alzheimer’s, the APOE4 variant and CAA, Blanchard, Tsai and co-authors coaxed human induced pluripotent stem cells to become the three types of cells that make up the BBB: brain endothelial cells, astrocytes and pericytes. Pericytes were modeled by mural cells that they tested extensively to ensure they exhibited pericyte-like properties and gene expression.

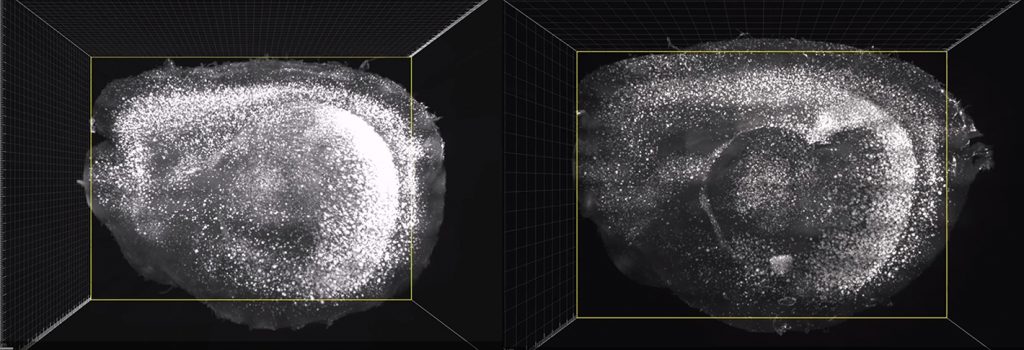

Grown for two weeks within a three-dimensional hydrogel scaffold, the BBB model cells assembled into vessels that exhibited natural BBB properties, including low permeability to molecules and expression of the same key genes, proteins and molecular pumps as natural BBBs. When immersed in culture media high in amyloid proteins, mimicking conditions in Alzheimer’s disease brains, the lab-grown BBB models exhibited the same kind of amyloid accumulation seen in human disease.

With a model BBB established, they then sought to test the difference APOE4 makes. They showed by several measures that APOE4-carrying BBB models accumulated more amyloid from culture media than those carrying APOE3, the more typical and healthy variant.

To pinpoint how APOE4 makes that difference, they engineered eight different versions covering all the possible combinations of the three cell types having either APOE3 or APOE4. When exposed these month-old models to amyloid-rich media, only versions with APOE4 pericyte-like mural cells showed excessive accumulation of amyloid proteins. Replacing APOE4 mural cells with APOE3-carrying ones reduced amyloid deposition. These results put blame for CAA-like pathology squarely on pericytes.

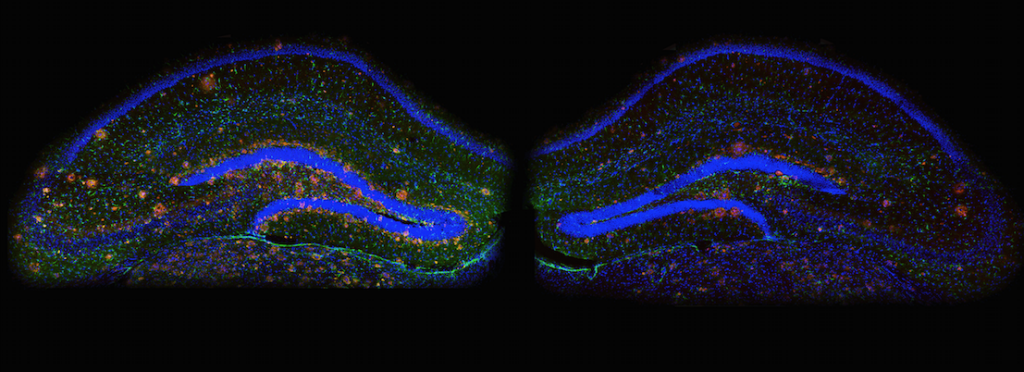

To further validate the clinical relevance of these findings, the team also looked at APOE expression in samples of human brain vasculature in the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus, two regions crucially affected in Alzheimer’s disease. Consistent with the team’s lab BBB model, people with APOE4 showed higher expression of the gene in the vasculature, and specifically in pericytes, than people with APOE3.

“That is a salient point of this paper,” said Tsai, a founding member of MIT’s Aging Brain Initiative. “It’s really cool because it stresses the cell-type specific function of APOE.”

A pathway toward treatment?

The next step was to determine how APOE4 becomes so overexpressed by pericytes. The team therefore identified hundreds of transcription factors – proteins that determine how genes are expressed – that were regulated differently between APOE3 and APOE4 pericyte-like mural cells. Then they scoured that list to see which factors specifically impact APOE expression. A set of factors that were upregulated in APOE4 cells stood out: ones that were part of the calcineurin/NFAT pathway. They observed similar upregulation of the pathway in pericytes from human hippocampus samples.

As part of their investigation of whether elevated signaling activity of this pathway caused increased amyloid deposition and CAA, they tested cyclosporine A and FK506 because they tamp pathway activity down. They found that the drugs reduced APOE expression in their pericyte-like mural cells and therefore APOE4-mediated amyloid deposits in the BBB models. They also tested the drugs in APOE4-carrying mice and saw that the medicines reduced APOE expression and amyloid buildup.

Blanchard and Tsai noted that the drugs can have significant side effects, so their findings might not suggest using exactly those drugs to address CAA in patients.

“Instead it points toward the value of understanding the mechanism,” Blanchard said. “It allows one to design a small molecule screen to find more potent drugs that have less off-target effects.”

In addition to Blanchard and Tsai, the paper’s other authors are Michael Bula, Jose Davila-Velderrain, Leyla Akay, Lena Zhu, Alexander Frank, Matheus Victor, Julia Maeve Bonner, Hansruedi Mathys, Yuan-Ta Lin, Tak Ko, David Bennett, Hugh Cam, and Manolis Kellis.

The Robert A. and Renee E. Belfer Family Foundation, the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, The National Institutes of Health, the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research and the American Federation for Aging Research funded the research.