Extra chromosome alters chromosomal conformation and DNA accessibility across the whole genome in neural progenitor cells, disrupting gene transcription and cell functions much like in cellular aging

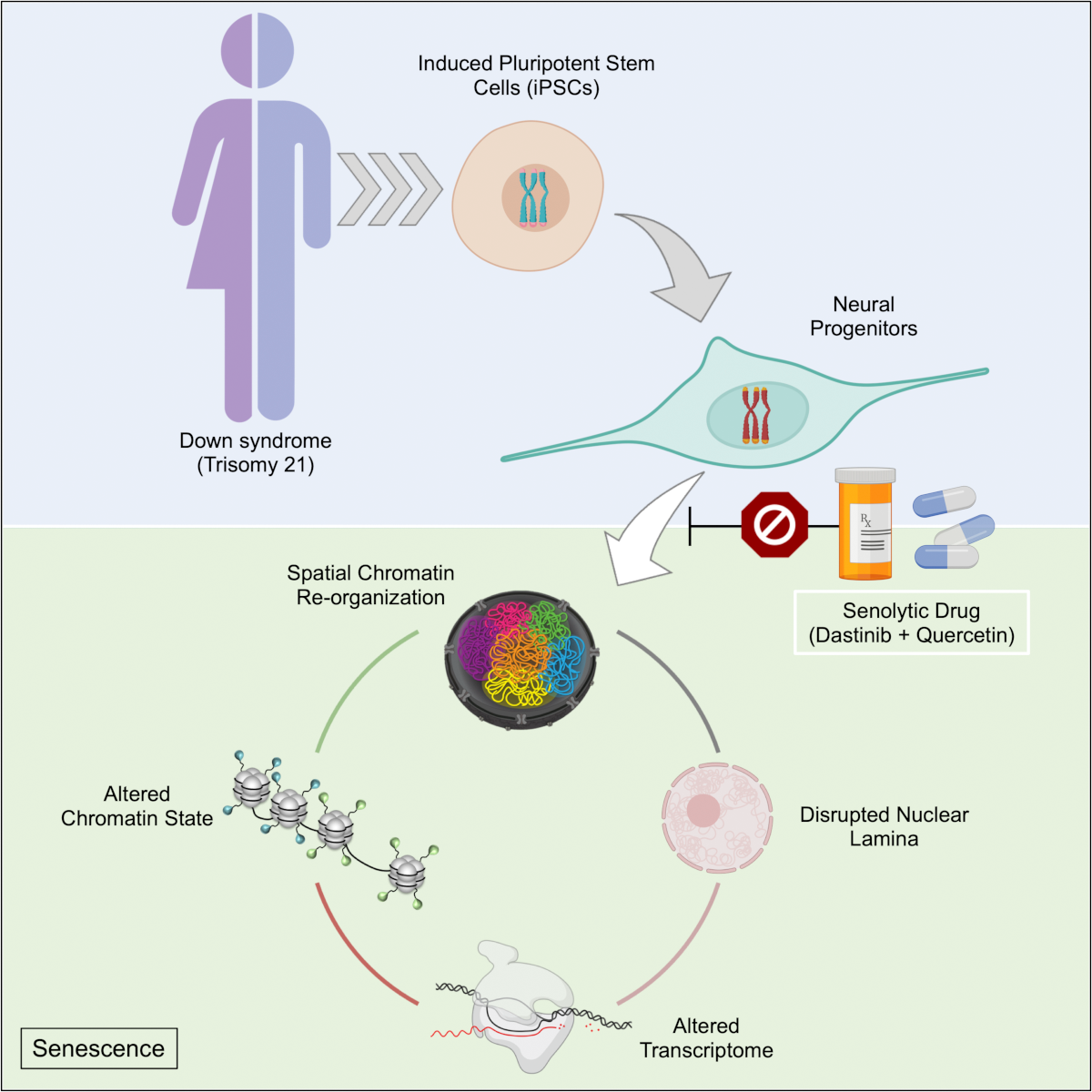

In Down syndrome, the third copy of chromosome 21 causes a reorganization of the 3D configuration of the entire genome in a key cell type of the developing brain, a new study shows. The resulting disruption of gene transcription and cell function are so similar to those seen in cellular aging, or senescence, that the scientists leading the study found they could use anti-senescence drugs to correct them in cell cultures.

The study published in Cell Stem Cell therefore establishes senescence as a potentially targetable mechanism for future treatment of Down syndrome, said Hiruy Meharena, a new assistant professor at the University of California San Diego who led the work as a Senior Alana Fellow in the Alana Down Syndrome Center at MIT.

“There is a cell-type specific genome-wide disruption that is independent of the gene dosage response,” Meharena said. “It’s a very similar phenomenon to what’s observed in senescence. This suggests that excessive senescence in the developing brain induced by the third copy of chromosome 21 could be a key reason for the neurodevelopmental abnormalities seen in Down syndrome.”

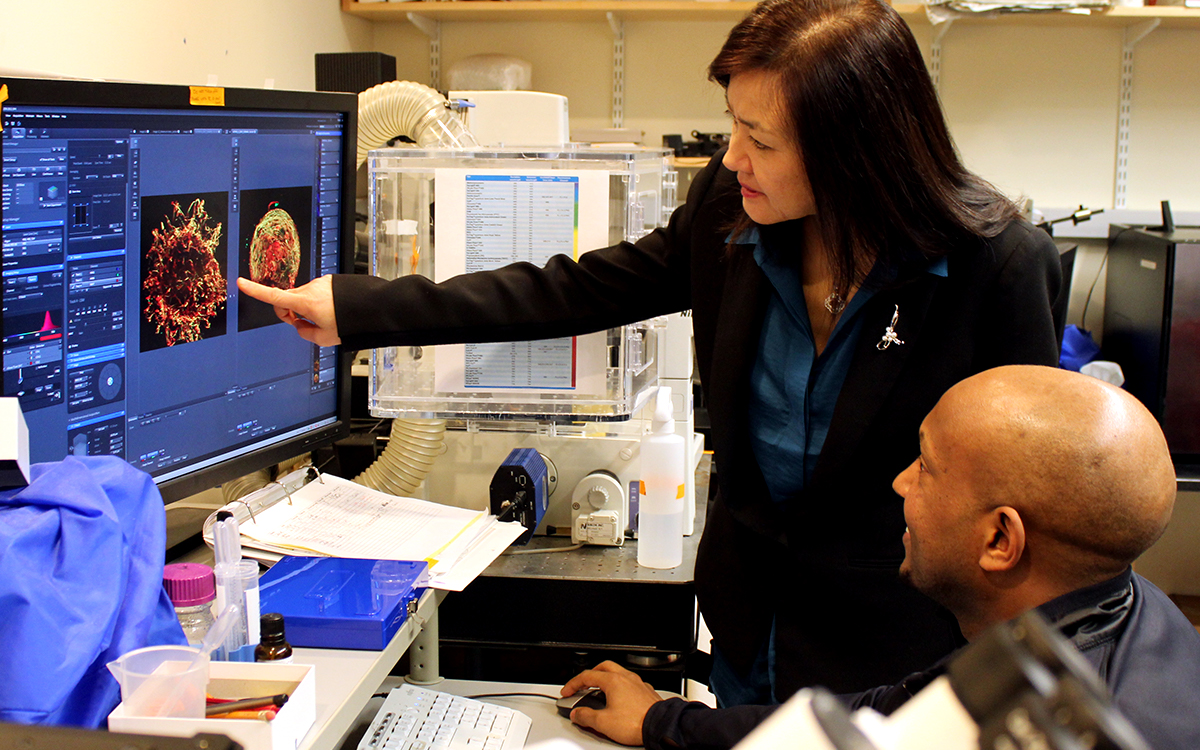

The study’s finding that neural progenitor cells (NPCs), which develop into major cells in the brain including neurons, have a senescent character is remarkable and novel, said senior author Li-Huei Tsai, but it is substantiated by the team’s extensive work to elucidate the underlying mechanism of the effects of abnormal chromosome number, or aneupoloidy, within the nucleus of the cells.

“This study illustrates the importance of asking fundamental questions about the underlying mechanisms of neurological disorders,” said Tsai, Picower Professor of Neuroscience, director of the Alana Center, and of The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT. “We didn’t begin this work expecting to see senescence as a translationally relevant feature of Down syndrome, but the data emerged from asking how the presence of an extra chromosome affects the architecture of all of a cell’s chromosomes during development.”

Genomewide changes

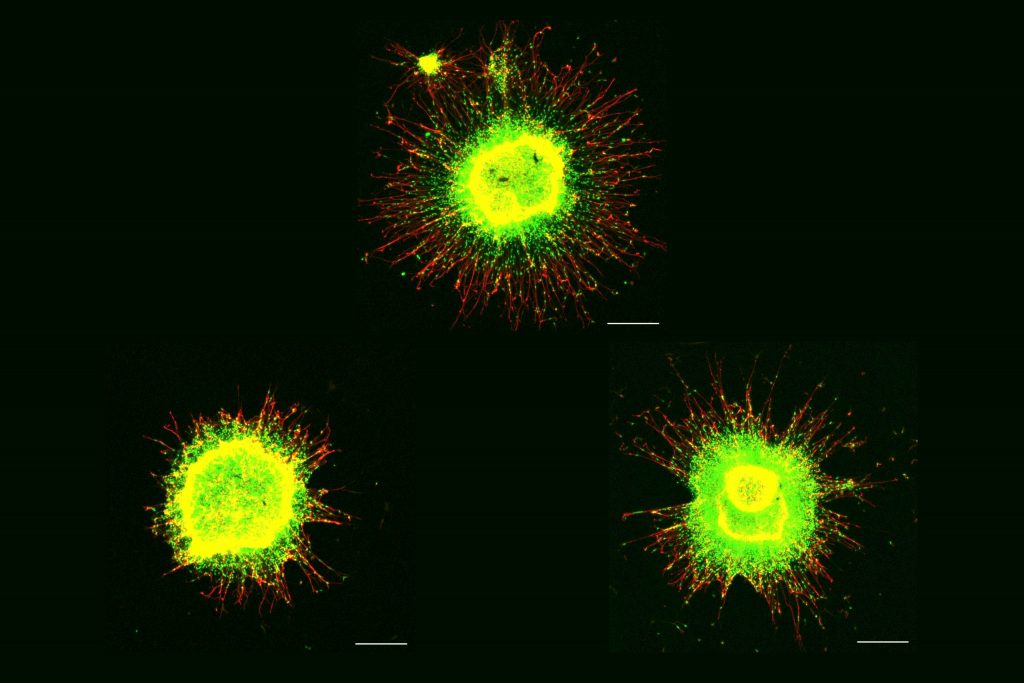

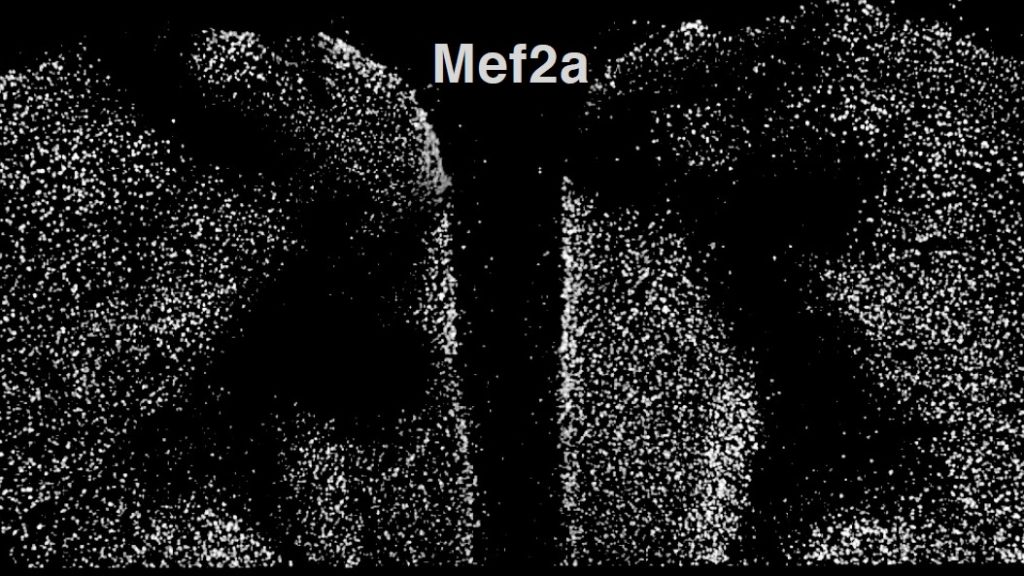

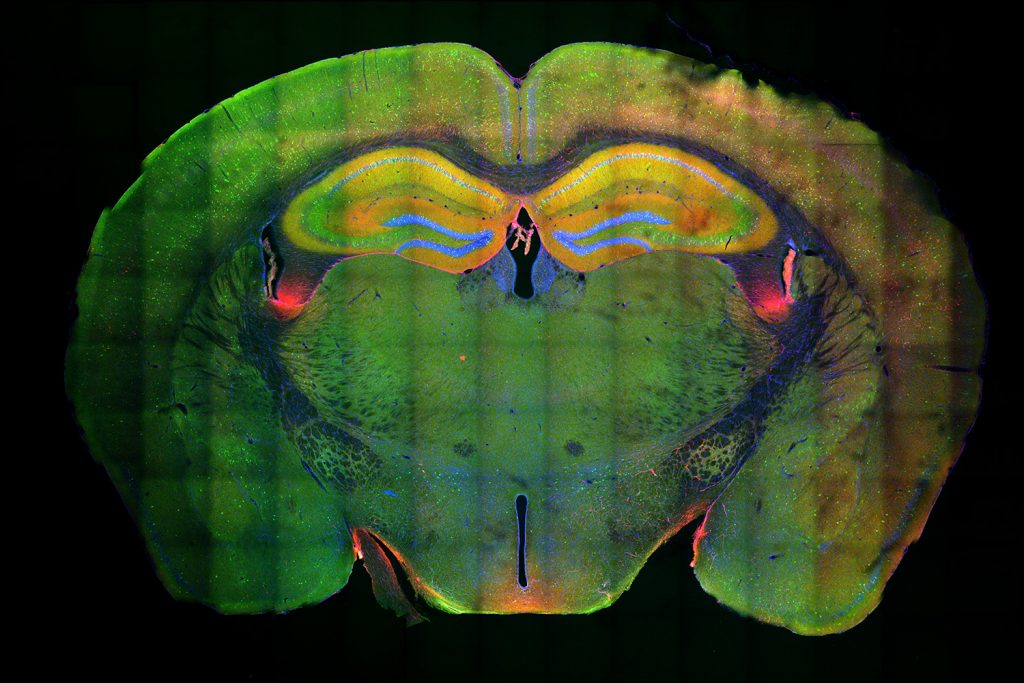

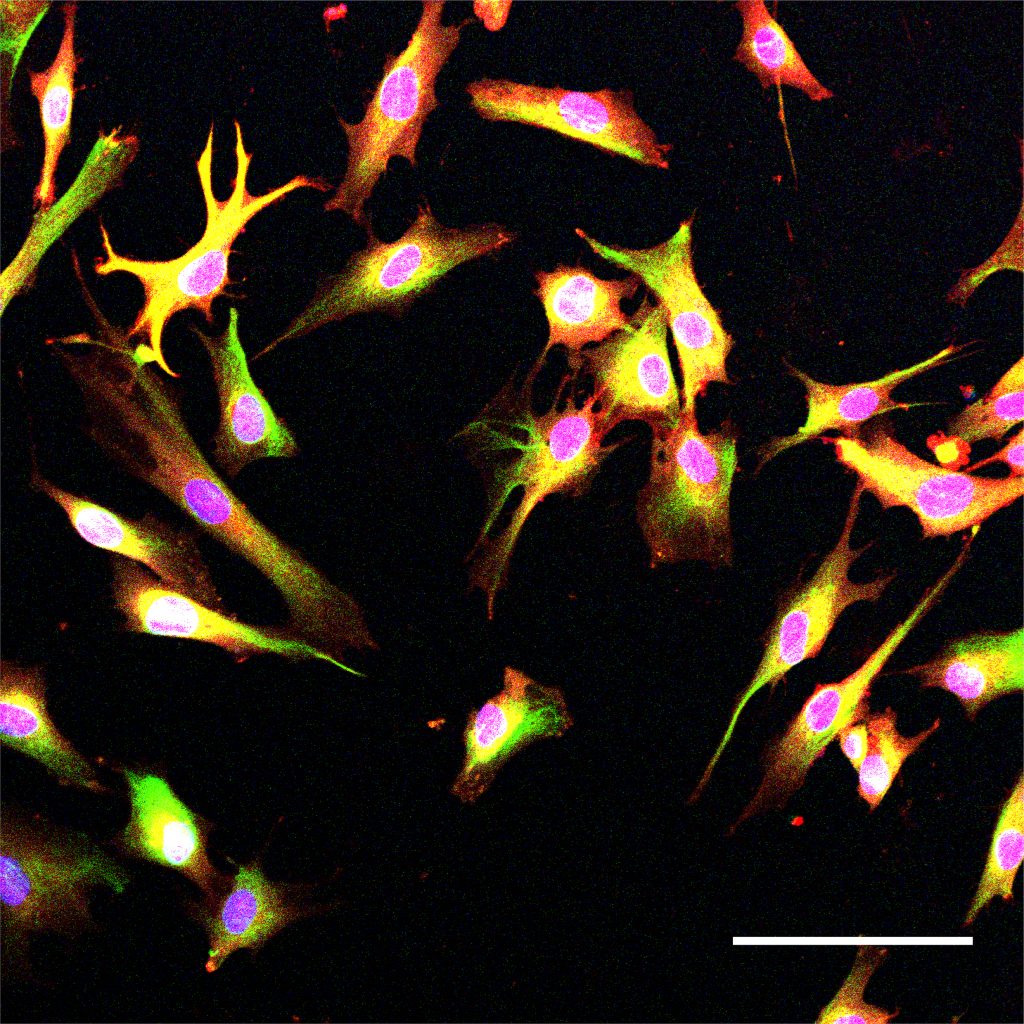

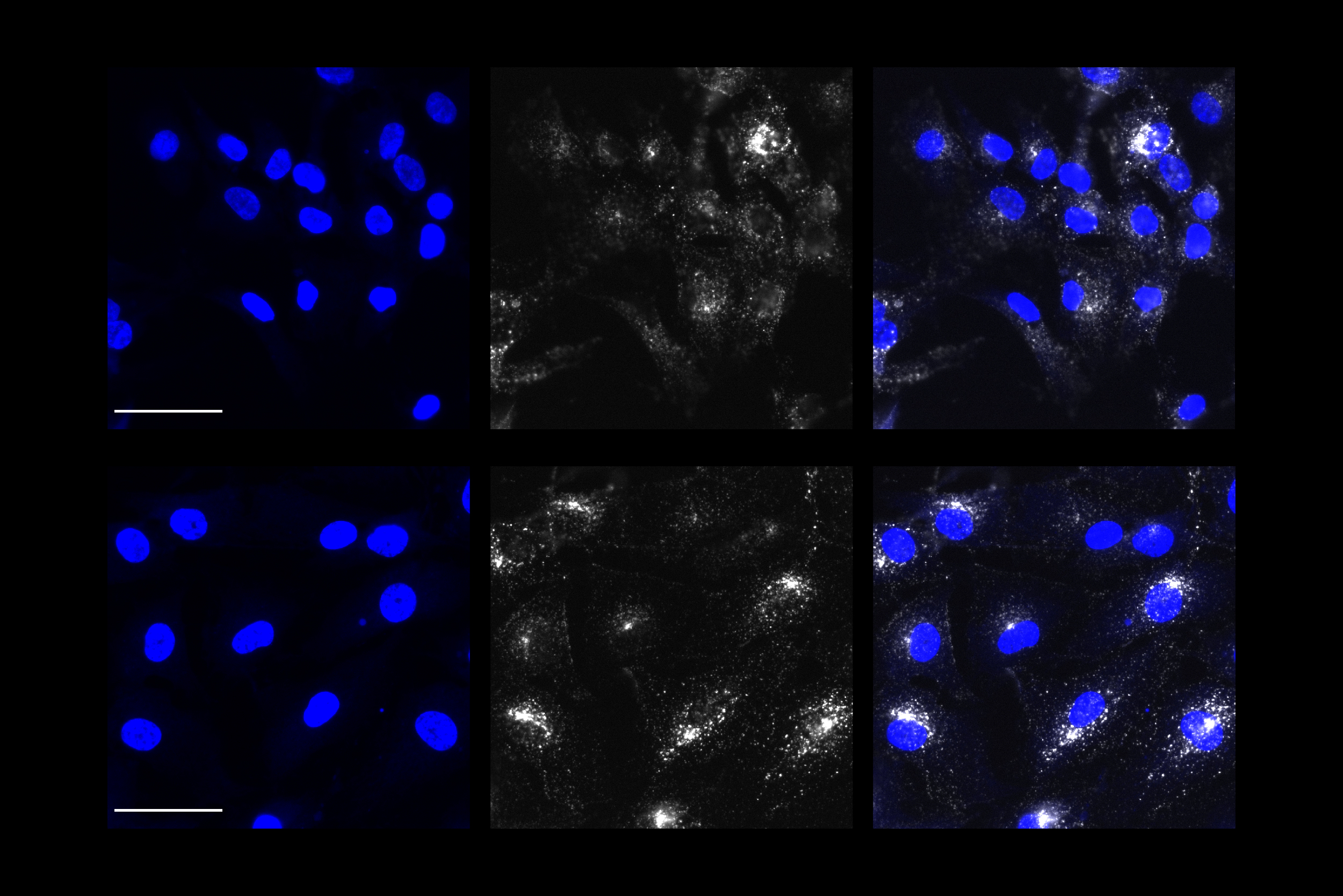

Meharena and co-authors spent years measuring distinctions between human cell cultures that differed only by whether they had a third copy of chromosome 21. Stem cells derived from volunteers were cultured to turn into NPCs. In both the stem cells and the NPCs, the team examined 3D chromosome architecture, several metrics of DNA structure and interaction, gene accessibility and transcription, and gene expression. They also looked at the consequences of the gene expression differences on important functions of these developmental cells, such as how well they proliferated and migrated in 3D brain tissue cultures. Stem cells were not particularly different, but NPCs were substantially affected by the third copy of chromosome 21.

Overall, the picture that emerged in NPCs was that the presence of a third copy causes all the other chromosomes to squish inward, not unlike when people in a crowded elevator must narrow their stance when one more person squeezes in. The main effects of this “chromosomal introversion,” meticulously quantified in the study, are more genetic interactions within each chromosome and less interactions among them. These changes and differences in DNA conformation within the cell nucleus lead to changes in how genes are transcribed and therefore expressed, causing important differences in cell function that affect brain development.

Treated as senescence

For the first couple of years as these data emerged, Meharena said, the full significance of the genomic changes were not apparent, but then he read a paper showing very similar genomic rearrangement and transcriptional alterations in senescent cells.

After validating that the Down syndrome cells indeed bore such a similar signature of transcriptional differences, the team decided to test whether anti-senescence drugs could undo the effects. They tested a combination of two: dasatinib and quercetin. The medications improved not only gene accessibility and transcription, but also the migration and proliferation of cells.

That said, the drugs have very significant side effects—dasatinib is only given to cancer patients when other treatments have not done enough—so they are not appropriate for attempting to intervene in brain development amid Down syndrome, Meharena said. Instead an outcome of the study could be to inspire a search for medications that could have anti-senolytic effects with a safer profile.

Senescence is a stress response of cells. At the same time, years of research by former MIT biology professor Angelika Amon, who co-directed the Alana Center with Tsai, has shown that aneuploidy is a source of considerable stress for cells. A question raised by the new findings, therefore, is whether the senescence-like character of Down syndrome NPCs is indeed the result of an aneuploidy induced stress and if so, exactly what that stress is.

Another implication of the findings is how excessive senescence among brain cells might affect people with Down syndrome later in life. The risk of Alzheimer’s disease is much higher at a substantially earlier age in the Down syndrome population than among people in general. In large part this is believed to be because a key Alzheimer’s risk gene, APP, is on chromosome 21, but the newly identified inclination for senescence may also accelerate Alzheimer’s development.

In addition to Meharena and Tsai, the paper’s other authors are Asaf Marco, Vishnu Dileep, Elana Lockshin, Grace Akatsu, James Mullahoo, Ashley Watson, Tak Ko, Lindsey Guerin, Fatema Abdurrob, Shruti Rengarajan, Malvina Papanastasiou and Jacob Jaffe.

The Alana Foundation, the LuMind Foundation, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, UNCF-Merck and the National Institutes of Health funded the research.